Imagine you're trying to have a clear conversation in a crowded, noisy room. People are talking over each other, music is blaring, and someone's dropped a pot in the kitchen. Suddenly, understanding even a single sentence becomes a Herculean task.

That's precisely what happens to your wireless signals when environmental factors and signal interference come into play. Your Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, cellular data, and even smart home devices rely on invisible radio waves to communicate. But these waves are constantly battling unwanted energy – "noise" – that degrades their clarity, making your intended information difficult, if not impossible, to receive. The result? Frustratingly slow internet, dropped calls, pixelated video, or unresponsive smart devices.

It's not just a minor annoyance; for critical systems, it can lead to communication failures, data loss, and even safety hazards. Understanding these invisible adversaries is the first step toward building and maintaining robust, reliable wireless networks.

At a Glance: Key Takeaways on Signal Interference

- What it is: Unwanted energy (noise) that degrades communication signals, causing issues like static or pixelation.

- How it's measured: The Signal-to-Interference-plus-Noise Ratio (SINR) quantifies signal quality.

- Three main culprits: Intentional transmissions (like competing Wi-Fi), accidental electrical byproducts (like microwaves), and physical environmental factors (like buildings or weather).

- Its impact: Data corruption, slow speeds, dropped connections, reduced battery life, and system instability.

- How to detect it: Spectrum analyzers, signal strength tools, and specialized error rate tests.

- How to fight back: Smart hardware (filters, advanced antennas, shielded cables), clever software (error correction, coordinated transmissions), and robust design principles.

- The future: AI and full-duplex communication promise more resilient systems.

Unmasking the Invisible Adversary: What is Signal Interference?

At its core, signal interference is the degradation of a communication signal by unwanted energy. Think of it as static on a radio or pixelation on a streaming video – symptoms that the "noise" is overpowering the "signal." This phenomenon affects any system that relies on electromagnetic waves, from your home Wi-Fi to satellite communications.

The quality of your wireless connection is often boiled down to a crucial metric: the Signal-to-Interference-plus-Noise Ratio (SINR). This ratio compares the power of your desired signal to the combined power of all the interference and ambient noise around it. A high SINR means a strong, clear signal. A low SINR, however, means your desired information is struggling to be heard amidst the cacophony.

Sources of this unwanted energy generally fall into three broad categories: intentional transmissions from other devices, accidental electrical byproducts from electronics, and natural physical environmental factors. Let's break down each one.

The Troublemakers: Main Categories of Interference

Understanding where interference comes from is crucial for effectively tackling it. These sources are diverse, ranging from your neighbor's Wi-Fi to a distant solar flare.

1. Intentional Transmissions (RFI): The Airwave Hoggers

Radio Frequency Interference (RFI) often occurs when multiple devices try to use the same frequency band simultaneously. It's like everyone in that noisy room trying to speak at once on the same topic.

- Co-channel Interference: This is perhaps the most common RFI culprit in dense environments. Imagine two or more Wi-Fi routers, operating in close proximity, all trying to use the exact same frequency channel. Data packets collide, leading to slower speeds and frustrating timeouts. This is why a simple channel change on your router can sometimes dramatically improve Wi-Fi performance.

- Adjacent Channel Interference: Even if devices aren't on the exact same channel, their signals can "bleed" into nearby frequency bands. A prime example is Bluetooth, which shares the 2.4 GHz ISM band with many Wi-Fi networks. A powerful Bluetooth signal can often spill over, causing slowdowns for your Wi-Fi, even if they're technically on different, but close, channels.

- Other Intentional Devices: Before Wi-Fi became ubiquitous, devices like older cordless phones and baby monitors often used frequencies like 900 MHz or 5.8 GHz. These can still generate strong signals capable of disrupting lower-power transmissions in their vicinity.

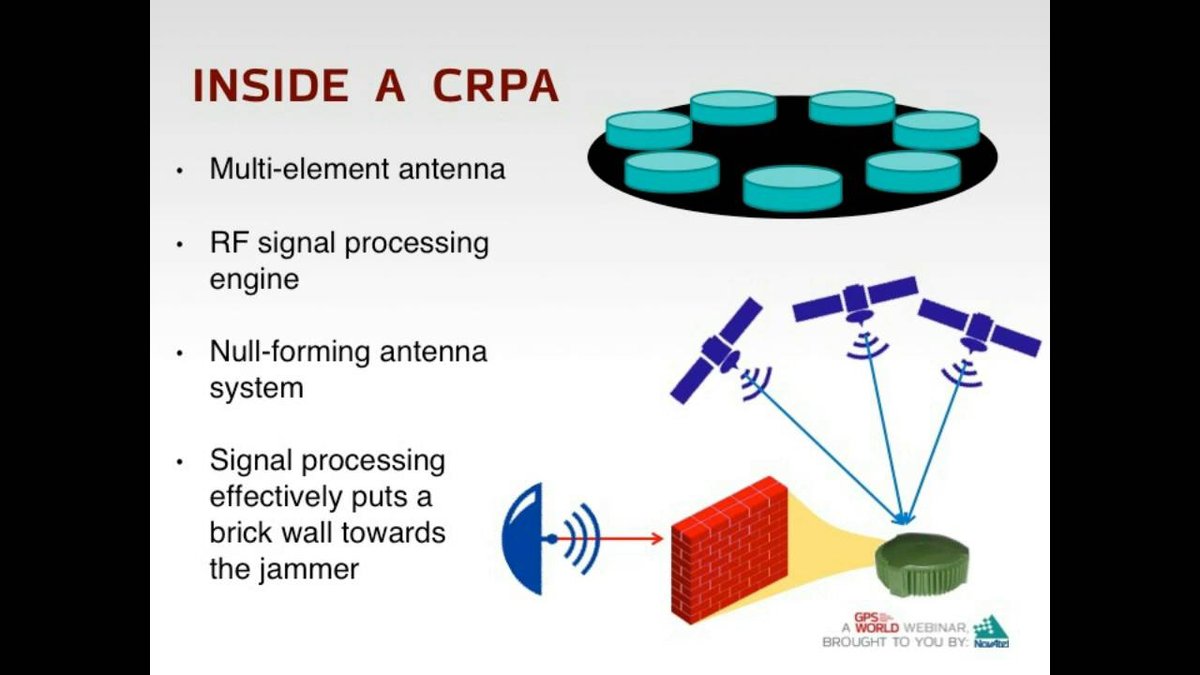

- Active Interference / Jamming: This is a deliberate and malicious act. A jammer emits strong radio signals on a specific frequency, overwhelming legitimate communications. Cellular phone jammers, for instance, are designed to decrease the SINR so drastically that phones can't connect, effectively causing a communication blackout or forcing devices offline. This type of attack isn't just an inconvenience; it can be a significant security threat.

2. Accidental Electrical Byproducts (EMI): The Unseen Static

Electromagnetic Interference (EMI) arises from electrical and electronic devices that unintentionally generate radio noise as a byproduct of their operation. This usually involves rapid current switching or electrical arcs creating transient electromagnetic radiation that couples into nearby antennas or wires.

- Household Devices: Your kitchen might be a hotbed of EMI. Microwave ovens, for instance, operate around the 2.45 GHz band, which is perilously close to your 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi. Imperfect shielding can cause significant signal leakage, leading to drastic Wi-Fi slowdowns when your microwave is running. If you find your Chromebook keeps disconnecting from WiFi when the microwave is on, interference is likely the culprit, and you might need to troubleshoot Chromebook WiFi disconnections more broadly.

- Electric Motors: Devices with electric motors, like blenders, vacuum cleaners, power tools, and even heavy industrial equipment, generate significant EMI. The sparking that occurs during motor commutation (the switching of current) creates broadband radio noise that can affect nearby electronics.

- Lighting and Power Systems: Fluorescent lights and certain LED fixtures, particularly those with electronic ballasts, are known to emit harmonic noise. Furthermore, poorly shielded or grounded power cables and the switching power supplies found in computers and chargers can contribute a general "hum" of ambient electromagnetic noise to your environment.

- Other Sources: Cables themselves can act as unintended antennas, picking up or radiating noise. Fans, commercial radio stations, and even microwave relay antennas used for long-distance communication can all contribute to the EMI landscape.

- Physical Phenomena: Beyond generated noise, power line issues can also disrupt. Overvoltage (due to utility anomalies, wiring faults, or lightning strikes) can destroy sensitive electronic components, while undervoltage (brownouts or power outages) simply interrupts service altogether.

3. Physical Environmental Factors: Nature's Obstacles

Sometimes, the environment itself is the biggest obstacle. These factors don't generate noise, but rather attenuate (weaken by absorption or scattering) or distort signals through multipath propagation (where a signal takes multiple paths to reach the receiver).

- Terrain and Structures: Mountains, large buildings, and even dense urban landscapes can physically block the line-of-sight between a transmitter and a receiver. This leads to weakened signals and can create "dead zones" where coverage is poor or nonexistent.

- Dense Foliage: Trees, bushes, and other dense plant life absorb and scatter radio waves, particularly at higher frequencies. This is why you might notice your outdoor Wi-Fi extender struggles more in the summer when trees are in full leaf.

- Severe Weather (Rain Fade): Rain, snow, and ice crystals in the atmosphere can absorb and scatter radio waves. This phenomenon, known as "rain fade," becomes more pronounced at frequencies above 10 GHz, impacting systems like satellite TV, high-capacity wireless backhaul, and 5G millimeter-wave deployments. Water molecules are particularly good at absorbing signal energy.

- Natural Atmospheric/Space Phenomena: Even nature on a grand scale can interfere. Lightning strikes generate intense, broadband radio noise that can temporarily disrupt communications. More dramatically, solar flares and other solar activity can cause magnetic disturbances in Earth's atmosphere, leading to temporary radio blackouts or significantly increased noise levels, especially for high-frequency (HF) radio communications.

When Signals Go Sideways: The Impact of Interference

The consequences of signal interference ripple through every aspect of wireless communication, transforming seamless operation into a frustrating ordeal.

- Data Corruption and Errors: At the most fundamental level, interference introduces errors into digital data streams. This leads to an increased bit error rate (BER), meaning more bits are received incorrectly. If too many errors occur, data becomes unusable, requiring retransmission and slowing everything down.

- Reduced Throughput and Instability: For networks like Wi-Fi or smart meter grids, interference directly translates to slower data speeds and unreliable connections. Devices struggle to communicate effectively, leading to dropped packets, network congestion, and general instability.

- Lower Spectral Efficiency: When interference is rampant, networks become less efficient at using their available frequency spectrum. This means they can transmit less data per unit of frequency, making it harder to serve many users or high-bandwidth applications.

- Increased Contention and Collisions: In ad-hoc networks, like many Wi-Fi setups, devices try to avoid transmitting at the same time. Interference can make it seem like a channel is always busy, leading to more Medium Access Control (MAC) layer collisions and wasted airtime.

- Communication Failures: In critical systems, interference can cause complete communication breakdowns. For smart meter networks or RFID systems, this can mean missing data points, inaccurate readings, and reduced read speed or range.

- Exhausted Batteries: In the case of jamming attacks, legitimate devices might try to compensate by increasing their transmission power to overcome the interference. This rapidly drains device batteries, shortening their operational lifespan.

- Analog vs. Digital: While digital signals can often recover from some errors through correction codes, severe interference can overwhelm these mechanisms. In analog systems (like old TV broadcasts), discrete signal interference often appears as visible parallel line patterns.

Diagnosing the Disruption: How to Detect and Measure Interference

You can't fix what you can't see or measure. Detecting and analyzing signal interference is a specialized skill, often requiring dedicated tools and sophisticated techniques.

Spectrum Analysis: The X-Ray for Your Airwaves

A spectrum analyzer is the cornerstone tool for interference detection. It acts like an X-ray machine for the electromagnetic spectrum, allowing you to visualize:

- Electromagnetic Wave Composition: What frequencies are active in your environment?

- Signal Strength: How strong are desired and undesired signals?

- Interference Signatures: Can you identify the unique "fingerprint" of different interference sources (e.g., the distinct pattern of a microwave oven)?

- Additive External Noise (AEN): The general background noise floor that affects all signals.

By observing patterns and spikes on a spectrum analyzer, experts can pinpoint the source and nature of interference.

Signal Strength Analysis & SINR Measurement

While a spectrum analyzer gives you the big picture, dedicated signal strength meters and software can evaluate the received power of specific signals. Crucially, they can help determine the SINR at different locations. If your signal is strong but your SINR is low, you know interference is the primary problem, not just weak signal coverage.

Bit Error Rate (BER) Testing

For digital communication channels, the Bit Error Rate (BER) is a direct measure of how much noise is affecting your data. A Bit Error Rate Tester (BERT) injects a known data pattern into a channel and then compares the received pattern to the original, counting any discrepancies. Modern local area networks (LANs) typically require a BER better than 10^-10 (meaning fewer than 1 error in every 10 billion bits) for reliable operation.

Anomaly Detection Algorithms

In complex networks like IEEE 802.11 Wi-Fi, manual detection can be overwhelming. Network Intrusion Detection Systems (NIDS) increasingly employ anomaly detection algorithms. These systems constantly monitor network traffic and signal characteristics (like frame intervals, Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI), sequence number gaps, and packet subtypes) to identify unusual behavior that might indicate:

- Jamming attacks: Sudden drops in RSSI or unusually high retransmission rates.

- Spoofing: Impersonation of legitimate devices.

- Fake Access Points: Unauthorized Wi-Fi networks designed to trick users.

Machine learning-based NIDS, utilizing algorithms like Random Forest, are proving highly effective, achieving precision rates of 99.80% for deauthentication attacks, 96.41% for detecting fake access points, and 82.12% for jamming.

Remote Interference Detection

Advancements in AI and deep learning are pushing the boundaries of interference detection. Remote systems using ensemble models and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can achieve identification accuracy up to 99%, allowing for proactive identification and management of interference across wide areas without needing on-site personnel.

Fighting Back: Strategies to Mitigate and Prevent Interference

Dealing with signal interference isn't a single solution; it's a multi-faceted approach combining smart hardware, intelligent software, robust security, and careful design.

A. Hardware-Based Solutions: Building a Stronger Foundation

Many solutions involve physical components designed to either block interference or enhance desired signals.

- Filtering Mechanisms: These are like bouncers for your signals, allowing only the desired frequencies to pass. Low-pass filters block high frequencies, high-pass filters block low ones, and adaptive filters can dynamically adjust to remove unwanted noise in real-time, significantly enhancing your SINR.

- Advanced Antenna Design:

- Beamforming: Antennas can intelligently steer their signal directly toward a receiving device, focusing power and reducing interference to other areas.

- Multiple Input Multiple Output (MIMO) Arrays: Using multiple antennas at both the transmitter and receiver significantly increases data throughput and can make systems more resilient to interference by offering multiple signal paths.

- Directional Antennas: Instead of broadcasting everywhere, these antennas focus power in a specific direction, both increasing range in that direction and reducing the chance of interfering with or being interfered by devices outside that beam.

- Multi-Sector Fixed Beam Antennas: A step beyond single directional antennas, these divide an area into multiple sectors, each covered by a focused beam, optimizing coverage and minimizing interference within a larger space.

- Transmission Power Control Algorithms: Intelligently adjusting the transmission power of devices can optimize throughput and mitigate interference. Devices don't need to shout if the listener is close, reducing their impact on others.

- Passive Suppression Schemes: This includes physically orienting antennas away from known interference sources or using radio frequency absorbers (materials that soak up electromagnetic energy) to dampen noise in specific areas.

- Circulators and Duplexers: In full-duplex systems (where a device transmits and receives on the same frequency simultaneously), these components are crucial. They isolate the transmit and receive chains, preventing a device's own powerful outgoing signal from overwhelming its sensitive incoming signal.

- Shielded Cables: For wired networks, EMI/RFI can still cause errors. Shielded twisted pair (STP) and coaxial cables offer better insulation against external electromagnetic fields than unshielded twisted pair (UTP) cables, protecting the data within.

B. Software & Protocol-Based Solutions: Smart Signal Management

Beyond physical hardware, intelligent software and communication protocols play a vital role in managing interference.

- Error Correction Codes: These are digital tools that add redundant information to data packets. Techniques like Forward Error Correction (FEC) allow the receiver to detect and correct errors without needing retransmission, while Cyclic Redundancy Check (CRC) helps detect errors, prompting retransmission if needed.

- Coordinated Multipoint (CoMP) Transmission: In cellular networks, CoMP allows multiple base stations to coordinate their transmissions. This can involve coordinated scheduling, beamforming, and even joint transmission (where multiple base stations simultaneously send the same data to a single user) to minimize interference between different transmit points.

- Interference Cancellation and Coordination Techniques: These advanced methods attempt to estimate the interference signals present and then actively cancel them out from the received signal. This requires accurate channel estimation and sophisticated signal processing.

- Hybrid Interference Management: Often, the best approach is a combination of strategies. Hybrid systems might combine interference avoidance, cancellation, and coordination methods (e.g., using beamforming training optimized with reinforcement learning) to adaptively manage complex interference scenarios.

- Countermeasures Against Jamming:

- Channel Hopping: Rapidly and randomly changing communication frequencies makes it difficult for a jammer to disrupt all channels simultaneously, though this can increase energy consumption.

- Random Transmission Times: Introducing randomness into when devices transmit can make it harder for jammers to predict and target communication windows, offering a moderate complexity, low-energy solution.

C. Security Measures: Protecting Against Deliberate Attacks

When interference is intentional, security becomes paramount.

- Encryption: Scrambling transmitted signals ensures that even if interference degrades a signal, the data remains unreadable to unauthorized parties.

- Authentication Mechanisms: Digital signatures and Message Authentication Codes (MACs) verify the integrity and authenticity of signals, ensuring they haven't been tampered with or originated from an illegitimate source.

- Frequency Hopping and Spread Spectrum Techniques: These techniques, which involve rapidly changing carrier frequencies or spreading a signal across a wider band, inherently make signals more robust against jamming and harder for adversaries to intercept.

- Antijamming and Antisspoofing: These involve specialized signal processing algorithms and hardware designed to detect and counteract deliberate disruption attempts, allowing legitimate communications to persist.

D. Robust Design Principles: Engineering for Resilience

Designing systems with interference in mind from the outset is the most effective long-term strategy.

- Redundancy: Building in redundant communication links, backup antennas, and resilient power supplies ensures that if one path is compromised, others can take over, maintaining service continuity.

- Resilience: This encompasses secure network architectures, secure storage and processing environments, and strict access control mechanisms. A resilient system can withstand and recover from various disruptions, including those caused by interference.

The Future of Flawless Communication: Emerging Technologies

The battle against signal interference is ongoing, and innovation continues to provide new tools and strategies.

- Full-Duplex Communication: This groundbreaking technology allows devices to transmit and receive data simultaneously on the same frequency band. If perfected, it could potentially double spectrum efficiency. However, it requires extraordinarily advanced self-interference cancellation techniques to prevent a device's own powerful outgoing signal from overwhelming its sensitive incoming signal.

- Machine Learning-Based Interference Prediction and Management: AI is rapidly evolving to predict and manage interference. Machine learning models can analyze vast amounts of network data, learn interference patterns, and dynamically adjust network parameters (like power levels, channel assignments, and beamforming weights) for intelligent, adaptive mitigation and optimized resource allocation. This moves from reactive troubleshooting to proactive prevention.

Your Action Plan: Ensuring a Clear Connection

Dealing with environmental factors and signal interference isn't just about understanding the problem; it's about taking concrete steps to ensure your communication systems remain robust and reliable.

- Conduct a Comprehensive Site Survey: Whether you're setting up a new network or troubleshooting an existing one, a professional site survey is invaluable. This involves using specialized tools (like spectrum analyzers) to map signal strength, identify interference sources, and characterize the electromagnetic environment. This upfront investment can save countless hours of frustration later.

- Optimize Your Environment:

- Wi-Fi Channels: Regularly check and adjust your Wi-Fi router to less congested channels. Many routers default to the same few, leading to co-channel interference.

- Device Placement: Move sensitive wireless equipment away from known EMI sources like microwaves, fluorescent lights, and large motors.

- Cable Management: Use shielded cables where appropriate, especially for long runs or in electrically noisy environments.

- Minimize Obstacles: If possible, consider the impact of dense foliage or new physical structures on line-of-sight communication.

- Leverage Smart Hardware: When upgrading, look for devices with advanced antenna features like MIMO or beamforming. For industrial or critical applications, invest in systems designed with robust filtering and passive suppression.

- Embrace Software Solutions: Ensure your network devices are running the latest firmware, which often includes updated error correction and interference management protocols. If available, enable features like DFS (Dynamic Frequency Selection) on Wi-Fi routers, which helps them avoid radar interference.

- Prioritize Security: For sensitive communications, encryption, authentication, and frequency hopping are non-negotiable. Regular security audits can identify vulnerabilities that could be exploited by intentional jamming.

- Consider Redundancy and Resilience: For critical systems, plan for backup communication links, redundant hardware, and robust power solutions. A single point of failure is an invitation for disruption.

- Stay Informed: The wireless landscape is constantly evolving. Keep an eye on emerging technologies like AI-driven interference management, as these could offer powerful new ways to enhance your network's resilience.

Ultimately, achieving a reliable and secure communication system in the face of environmental factors and signal interference requires a holistic approach. It's about integrating hardware, software, security strategies, and smart design principles. By understanding the challenges and applying these solutions, you can transform your communication experience from a noisy struggle into a clear, consistent conversation.